The Golden Eagles- Building on funds of knowledge and reflecting on migration journeys

By Zoë Welsh

The Golden Eagles’ flight from Afghanistan was sudden, shocking and irreversible. The children had no agency in what was happening to them (Vervliet, 2015) and although they understood that it wasn’t safe to be in Afghanistan, that knowledge doesn’t obliterate the pride and affection they have for their country. I felt that it was imperative to try to acknowledge that, and to give the children opportunities to show pride in their country, culture and customs, as well as to develop a sense of hope (Arnot and Pinson, 2005) about the future. From the first day, children would doodle, draw and colour the Afghanistan flag on scrap paper, on their books and on labels and name cards. Taking my cue from them, I began to find ways of using this pride and affection for Afghanistan in their learning.

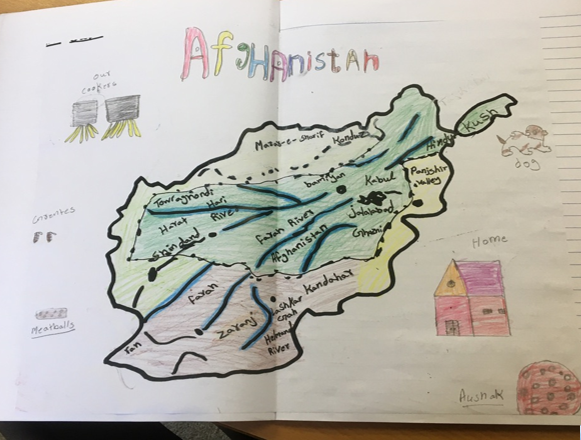

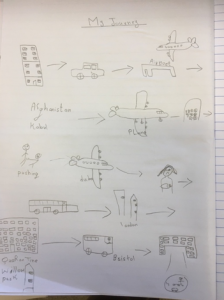

It is important to consider what we mean by inclusive education. In order for all pupils to be included in terms of their educational, social and emotional needs we need to respond to diversity and personalise the learning (Taylor and Sidhu, 2012). As such, I felt it was more important to build on the children’s interests and their position as newly arrived transnational pupils than try to adapt the main school curriculum to their needs (Hek, 2005). I focussed on ‘bridging school with the realities of families and communities,’(Bajaja and Bartlett, 2017).The children drew, labelled and coloured maps of Afghanistan that showed their cities and maps of Europe and Asia that showed Afghanistan and the UK. They were able to map their flight path from Kabul to Abu Dhabi, over Italy and France, to land in Birmingham in the UK.

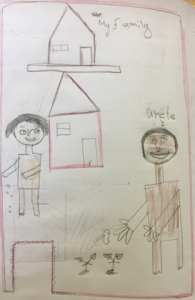

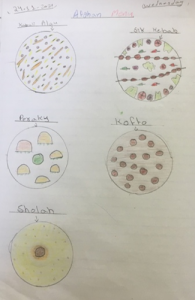

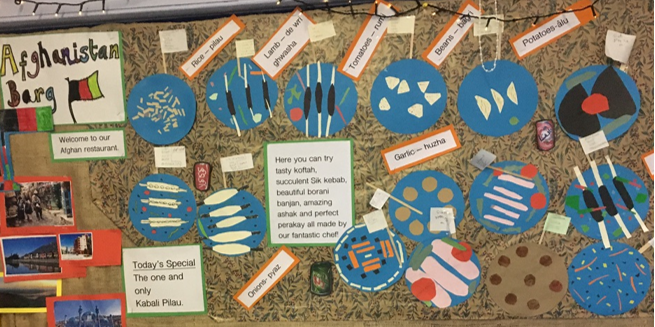

Moll (2019) considers that separating identity from the building of knowledge is not possible so using existing funds of knowledge is essential to move the children forward. I wanted to acknowledge, from the start, that the children would be developing identities as Afghans living in the UK, and to support this development with a transnational curriculum. I taught the English names for the Afghan food the children loved and missed and they found out the names of the ingredients. We drew pictures of different kinds of homes in Afghanistan and learned the English words for the colours and shapes of them.

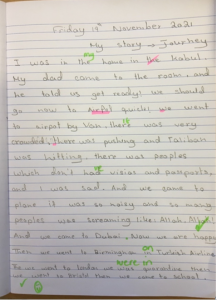

Moll also refers to ‘dark funds of knowledge’ (2019) which are the difficult experiences and feelings the children bring to school with them. I wanted to acknowledge and validate the experience of the children being evacuated from Kabul when and if they were ready to refer to it.

The Journey

Sharing a story can often be a way of broaching a difficult subject. I had several children’s books about migration and chose The Journey because the migrant family in the story use several different modes of transport and I wanted to start our Journey topic by learning the vocabulary associated with different modes of transport. We drew and labelled diagrams of bicycles, motorbikes, cars, vans, lorries, boats, submarines and helicopters. We made models from plasticine and then from clay. The children loved the freedom of making junk models too.

When the children had been in school full-time for a month, I started to show them some of the illustrations from The Journey avoiding the very first part of the story . We talked about the emotions in the characters’ faces – sad, angry and happy. We mapped out the journey that the characters made in the book.

I didn’t show the pictures of the big ‘war monster’ until the children knew that there was a positive ending to the story. We spent some time looking at the illustrations of the characters’ worlds turning, literally, upside down. Then we looked at the black shape with hands looming over the picture of the happy family at the beginning of the book.

The children described the picture as a monster (there was a lot of use of the bilingual dictionaries in this session).I tentatively used the word ‘war’ and they agreed that war was like a monster. We agreed on the term ‘war monster’.

This book allowed the children to respond creatively to their experience of leaving their homeland. The collages they made allowed them to consider what had happened and what they had left behind and mapping their own migration journeys gave them an opportunity to share their memories with each other and fill in things they’d forgotten.

These activities were an opportunity for creative expression which can have positive emotional benefits (Sullivan and Simonson, 2016). When the next group of Afghan children arrived a few months later, the original children were keen to share their work and provide an opportunity for them to map their own journeys. Subsequently, we have been joined by Ukrainian children who have also mapped their journey from the war in Ukraine to the UK.

Flexible planning

The timing of this kind of work is critical. My experience tells me that it’s important that children’s interests and everyday lives, before they left their home country, are used as a starting point for all learning, hence the work on their everyday life in Afghanistan, before the crisis.

It’s important to be flexible and take your cues from the children. Rae (2003) says ‘some will want and need to talk straight away, others will not, and may need time to process their experiences or do so in more creative ways through play, art, and creative outlets’. She argues that well meaning adults often get it wrong by always approaching a child with sympathetic questioning about their migratory experience when actually they would rather talk about football. In fact, it is extremely important to not ask too many direct questions and to be open to changing direction if the children are not responding. Some questions I used when talking about the journey were:

‘Would anyone like to say how this picture makes them feel?’ and ‘This reminds me of…. Would anyone like to say what they are reminded of?’

Having the refugee children together in a class and following a bespoke curriculum allows a safe space for this kind of work with children they know well and seems to help the children to hold the memories together and share the burden between them. It’s been a privilege to be able to support the children in this way.

Next time: Under the Same Sky – our work comparing the people, place and history of Bristol and Kabul.

References

Arnot, M. and H. Pinson. (2005.) The Education of Asylum Seeker and Refugee Children. A study of LEA and School Values, Policies and Practices. Cambridge, UK: Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

Bajaj, M. & Bartlett, L. (2017),”Critical transnational curriculum for immigrant and refugee students”, Curriculum inquiry, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 25-35.

Hek, R. (2005) The role of education in the settlement of young refugees in the UK: The experiences

of young refugees, Practice, 17(3), 157–171.

Moll, L.C. (2019) “Elaborating Funds of Knowledge: Community-Oriented Practices in International Contexts”, Literacy research, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 130-138.

Sullivan, A.L. & Simonson, G.R. 2016, “A Systematic Review of School-Based Social-Emotional Interventions for Refugee and War-Traumatized Youth”, Review of educational research, vol. 86, no. 2, pp. 503-530.

Rae, T (2022) How to Talk with Children and Young People About War | Understanding and Supporting our Refugee Children

https://www.evidenceforlearning.net/dr_tina_rae_children_war_refugees/

Taylor, S. & Sidhu, R. (2012) Supporting refugee students in schools: What constitutes inclusive

education?, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(1), 39–56.

Vervliet, M., Vanobbergen, B., Broekaert, E. & Derluyn, I. (2015) The aspirations of Afghan unaccompanied refugee minors before departure and on arrival in the host country, Childhood, 22

(3), 330–345.

0 Comments